“Osprey’s long, crooked wings may in fact be an adaptation to withstand the jolting impact of a large bird striking water.” — Birds of Prey: Hawks, Eagles, Falcons, and Vultures of North America by Pete Dunne, Kevin T. Karlson.

Osprey “Breeding pairs may be solitary or —where food is plentiful and suitable nest sites are few but clustered-birds may form loose breeding colonies, which provides a greater degree of nest defense and perhaps offers adults greater freedom to forage.” — Birds of Prey: Hawks, Eagles, Falcons, and Vultures of North America by Pete Dunne, Kevin T. Karlson.

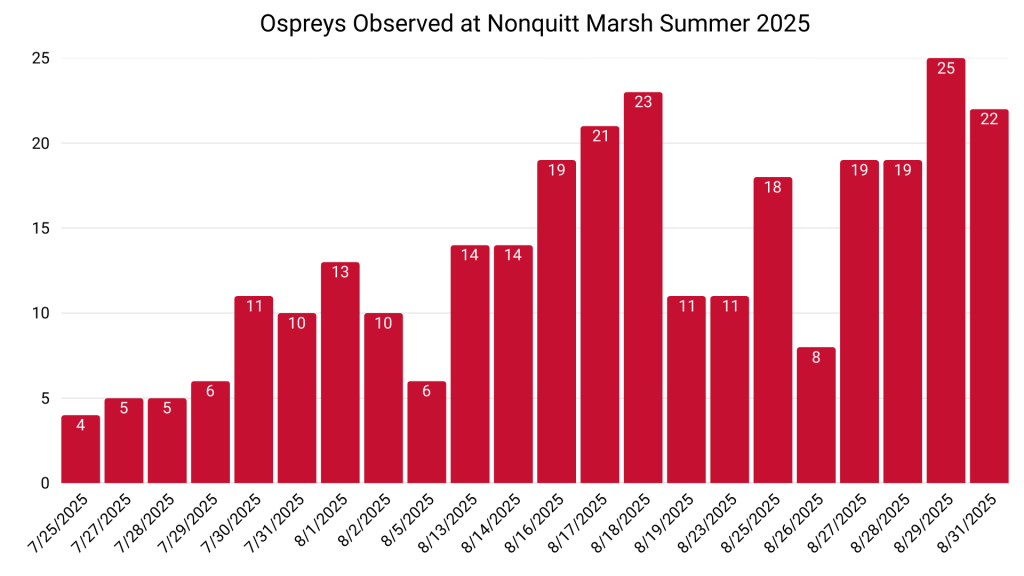

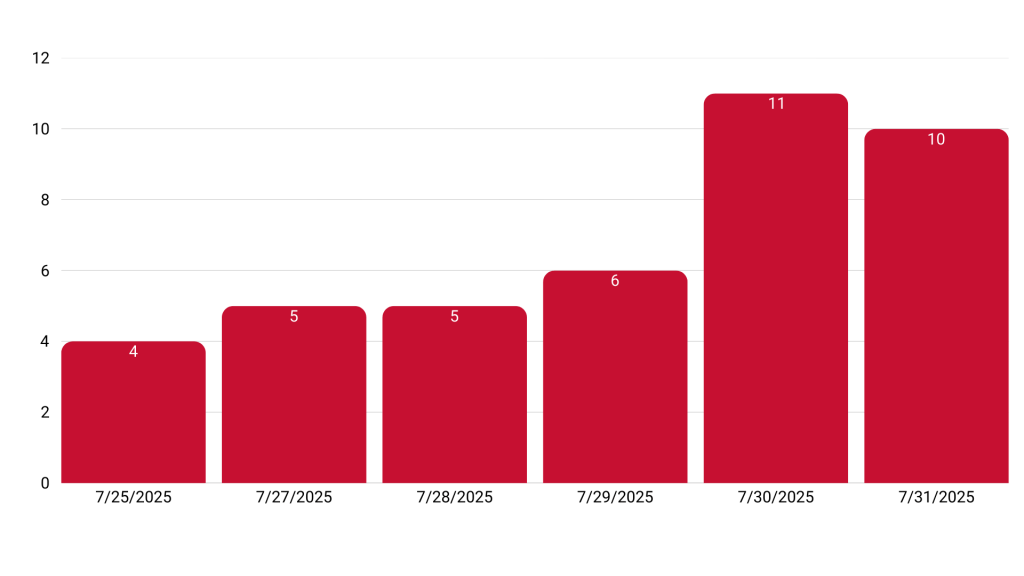

Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) data was not collected until July 25, but appears in its entirety below. OSPR03.

Summer 2025

Late July had birds separated in small clusters, a few Ospreys at the north and northwest edges, with the front treeline largely vacant. Observed interactions were minimal until July 29, when one Osprey displaced another from a perch. On July 30, numbers climbed to double digits across the front, north, and northeast trees. OSPR05.

August. Similar numbers were held in early August, mainly divided among the front, north, and northwest trees. On August 13, a flock of gulls clashed noisily with several Ospreys circling overhead. Ten birds clustered together in one tree, and others fed nearby. By August 14, at least 14 were present, with many arriving and vocalizing from the south. August 16 totaled 15 Ospreys in the front trees alone, with more in the north and northwest stands. Many were stuffed with fish, sunning themselves, wings held open or bent at curious angles. They are always eating. From that point on, counts regularly exceeded 20. On August 17, 21 Ospreys were recorded, and hunting behavior became more visible. Diving attempts were observed at close range for the first time. Great photo [OSPR06] taken by Stephen Petto at the Marsh on August 22.

A summer record 25 were counted on August 29 [OSPR07]

Fall 2025

September. September 1. Fall began with a bang. Twenty-seven Osprey. A 2025 record. There was non-stop circling and calling. Very active. On the evening of September 2, a Bald Eagle glided in lazily, and 11 Osprey took to the air, screaming. Two even dive-bombed the Eagle after it landed. Their argument heard. BAEA09.

September 3 brought 21 Osprey, a bird that frequently shifts their perches. Perhaps they’re so shifty because they can be ambushed by Common Ravens and more often, American Crows. OSPR08.

On September 6, 25 Ospreys were active, some carrying very large fish. Ospreys seem like relatively efficient hunters because they’re always carrying or standing on top of fish. A 2010 study, “Fishing behaviour of the Osprey Pandion haliaetus in an estuary in the northern Iberian Peninsula during autumn migration“, by Aitor Galarza, looked at “The fishing behaviour of the Osprey Pandion haliaetus in an estuary in the northern Iberian Peninsula during autumn stopover is described. All prey consisted of fish of the family Mugilidae (grey mullets) and overall fishing events lasted on average 6.3 min with a 68.8 % success rate (n = 61 fishing events). Adults were better fishers (92% of success) than young birds (40%). The occurrence of fishing events was independent of tidal period or tidal direction. However, fishing success was higher when the tide was rising.” Hell yea, Ospreys.

It’s a great looking bird. OSPR09.

The mass exodus really took place during the weekend of September 12. OSPR10.

While many winged southward, a few, presumably timid youths, stuck around. Some even went for a float. OSPR11.

On September 15, a Bald Eagle arrived and was immediately chased, dive-bombed, and screamed at by one of the 5 Osprey present—an intense, brief confrontation. There’s a noncommittal nature to Osprey Eagle in-flight interactions. They maintain a distance that’s close enough to be serious but not close enough to spark violence.

The gathering of the Nonquitt Marsh Osprey enters its drawn-out ending. Each day, there are a few fewer Osprey. Sometimes the Marsh can be very quiet, but on days with little wind, it can be quite noisy. Noisiest species, in no particular order other than the fact they’re all tied for first place for being annoying, are catbirds, willets, red-winged blackbirds, yellow legs of either leg length variety, but never Osprey. They’re all quite vocal, but it never grates.

On October 11, the last day I kept notes, there was one cold, lonely Osprey lingering. Go south, youngling.

The fall contains a massive gathering of Ospreys. Once they’re fledged and with so much good fish around, they really enjoy hanging out and socializing. With migration about over, I’ll miss their loud calls. The ones that shrillly introduced themselves to their compatriots as they glid into the Marsh off a sea breeze. They truly are a joy to watch. OSPR12.

Until the spring. Can’t come soon enough. OSPR13.

Leave a reply to Pre-Season Bird Report – Birds Birds Birds Cancel reply